Demons, Superstition & Folk Belief

Introduction

Irene Keller is quite the witch. Well, according to my standards this is a compliment of course. But rewind a few hundred years and she would have ticked every box of the Medieval witch-hunt handbooks: she lives in a huge, ancient farm in the remote borderlands of Northern Austria. There, in the outskirts of a tiny village, surrounded by valleys and forests, she goes about her business of collecting rare magical artefacts. Once you see her standing next to her favourite piece, an authentic old Schwurschädel (oath skull), all dressed in black, hidden behind long red curls, you quickly feel some of the authentic passion she so easily exudes for all things related to authentic Western folk-magic.

Irene Keller

Cultural activist, curator, host & researcher

In 2014 she and her husband single-handedly pulled off an amazing feat: Due to the significance of their private collection - and given they run a cultural centre in the ground floor of their large farmhouse - they were invited to contribute to the national exhibition on superstition. The result was not only an unprecedented exhibition on many facets of German-Austrian folk-magic and -belief but also a massive 400 page catalogue, detailing many historic artefacts, background stories as well as regional family ties and relationships.

Luckily for anybody who missed the original exhibition Irene Keller decided to give you a second chance: the follow up exhibition 'Demons, Superstition, Folk-Belief' (Dämonen, Aberglaube, Volksfrömmigkeit) is still running until October 2017. For anybody who still needs some convincing to shift their summer vacation plans on short notice and prioritise Austria or Bavaria, let me take you on a heavily abbreviated virtual tour of some of the most stunning artefacts of the collection.

Before we do that though, let's take a moment to acknowledge the massive amount of work that has gone into this project by Mrs and Mr Keller. If not for people like them much of these artefacts by now would be scattered and lost in either large national or small private collections. Either way, they would never see the light of the public eye again - and certainly not in such an amazingly curated and presented way as they currently do in the romantic Kulturgut Hausruck.

While the UK has dedicated places such as the Museum of Witchcraft, nothing comparable today exists in the German speaking countries. In a region so rich in magical lore and practice Irene Keller's work is the true work of the adept: working in service to the magical community and ensuring the gates of the temple remain open - even if they hide behind the look of a huge old, rose covered Austrian farmhouse.

LVX,

Frater Acher

Kulturgut Hausruck

Host of 'Dämonen, Aberglaube, Volksfrömmigkeit'

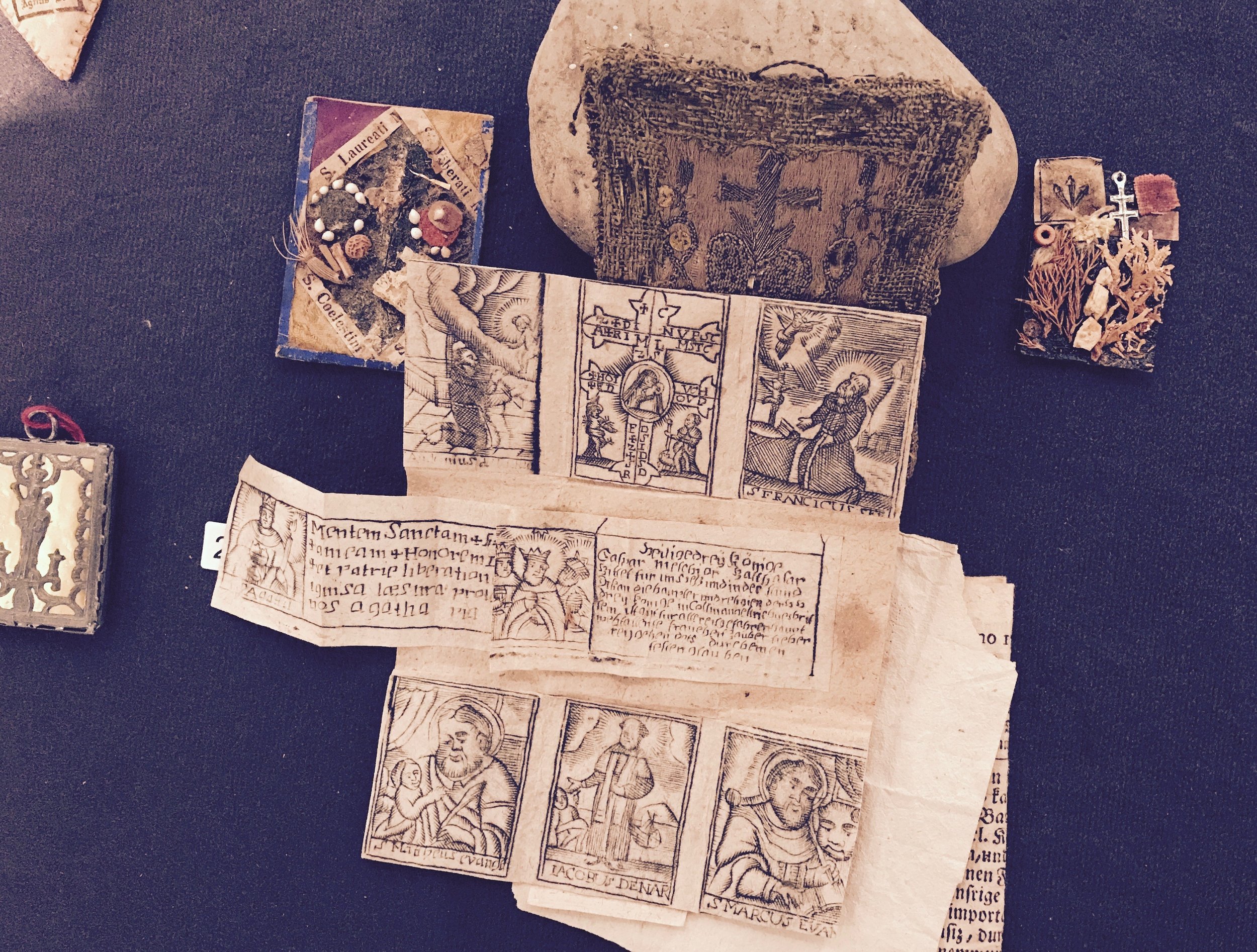

1. Relics

In one way or another the majority of magical acts in folk-belief involve the power of relics. Now, as we explored in our recent field trip to Beuerberg Abbey, it is important to broaden our stereotypical understanding of relics only relating to the deceased bodies of saints. Literally any substance could be turned into a 'relic'. Specifically the Catholic Church distinguishes three categories of relics:

- first category: the actual body, blood or ashes of the deceased;

- second category: objects that had been worn or touched by the deceased, such as clothes or e.g. torture tools for martyrs;

- third category: and finally any object that had been touched by and physically 'soaked up' the spirit of a relic - in particular paper or pieces of cloth placed on relics of the first category.

By the time we reach the Middle Ages a whole prospering economy had been built up around all three categories of relics. After all they were not only essential for folk-magic, but more importantly themselves considered critical agents to achieve spiritual purity and healing. Of course it also came in handy, that once the body of a martyr or saint had been dismembered and its parts spread out across Europe, nobody could actually validate anymore whose hair, bones or ashes a church held in their altar.

“relic (n): early 13c., ‘body part or other object from a holy person’, from Old French relique (11c., plural reliques), from Late Latin reliquiæ (plural) ‘remains of a martyr’, in classical Latin noun use of fem. plural of reliquus ‘remaining, that which remains’. Sense of ‘remains, ruins’ is from early 14c. Old English used reliquias, directly from Latin.”

The most pragmatic way, however, to think about relics is in form of a simple trade deal or actually a pact: two parties were involved, both of them wanting something, and both of them needing to give some to receive some. The devoted Catholic pilgrim classically would need to bring a votive offering, may it be carved from wood (see third image below) or cast from favourably red wax (fourth image). This offering was a gift to the respective saint or deity to whom their veneration and plea for help was addressed. The votive offering itself alone, however, was not enough; instead like so often in magic it was a mere representation of a more important act of service. And that act was the pilgrimage itself - the trouble and time it took back then to travel to the city, church or shrine of the saint - before one was able to place an actual votive offering on their threshold. It was the physical labor and devotion charged into the substance of the offering which created the currency pilgrims had to offer up to the spirits as their end of the deal.

While this might seem naive to academics today, it does remind us of an essential aspect in most shamanic traditions: Spirits by definition are highly obstructed in impacting the physical plane. Most of them only get mediated access to the physical realm. Just like we use them to receive impact on the spiritual realm, so they leverage us, humans to gain impact on the physical plane. Uncountable 'acts of service' which shamans carry out for spirits address precisely this dilemma: the spirits need to have a certain rock moved, a certain herb burned, a river re-directed, or simply a certain tune sung with a physical voice. In light of such ancient relationships between spirits and humans, the act of a pilgrimage and bringing a votive offering as a token and symbol of this journey, turns into a deeply shamanic act.

And another aspect should be mentioned here: The vast majority of votive offerings consisted of a symbolic representation of one's particular body part that required healing. Thus placing such a wax-cast or wood-carving of one's body on the altar of the spirit, the pilgrim offered up an actual part of themselves to the spirit - and officially gave it permission to enter into their body.

Now, the other side of the deal obviously sat with the spirit. The Latin saying 'Manus manum lavat.' (one hand washes the other) is obviously not only reserved to humans. The spirit (i.e. saint or deity mostly in this context) had to give a symbol of consent to partner and align to the human's wish as well. And this is where relics come in very handy. The idea to literally give a piece of your own (dead) body cannot be trumped as a symbol of commitment. Unfortunately our saint's bodies could not continue to 'give' for centuries; and it was even harder to request such a physical act of commitment or support from a deity that had never been human. Nevertheless, the idea to absorb the 'body of the spirit' still remained very much alive in Western folk-belief. After all, as Austin Osman Spare reminded us all almost a century ago, making the spirit turn into flesh (Zos Kia) really is the only trick a magician needs to master.

So unsurprisingly it is here we encounter the full color and texture of folk-belief: As you can see on the images below there were manifold ways of first creating a placeholder for the imagine body of the spirit - and then to absorb it by a human body. Over centuries two simple methods maintained the most significant fame and fellowship amongst Europeans:

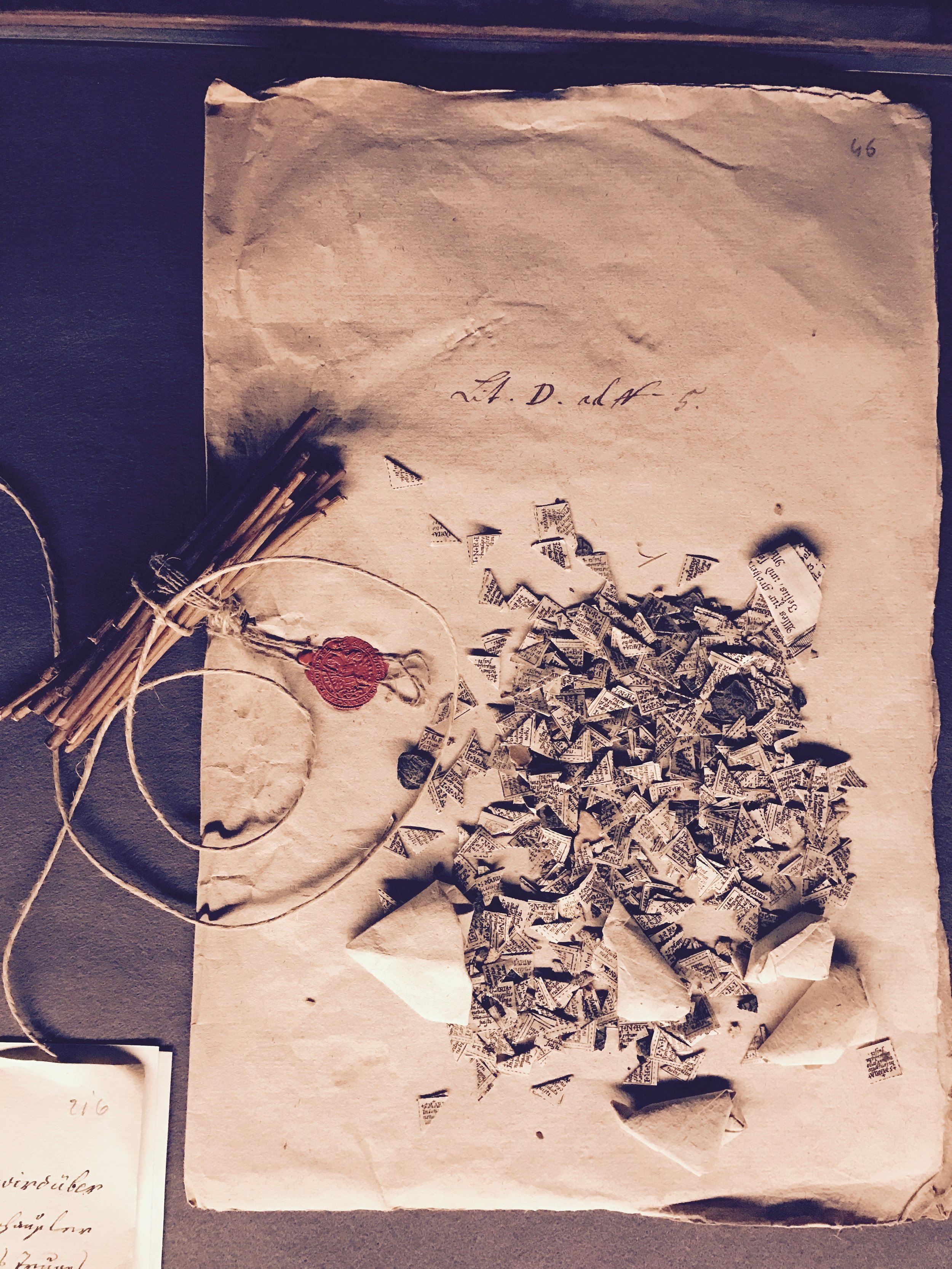

- The first is called 'Esszettel' or 'Schluckbildchen' in German, which is translated as 'editable images or chits'. These were thin strips of paper, mostly sold in blocks, and about the size of a stamp. Most of them were of cheap quality - unsurprisingly considering their use - and in raw black and white prints depicted either deities, saints or important acts of their lives. By ripping a single chit off the block, chewing, swallowing and digesting it the power of the blessed image was meant to become 'flesh' within the pilgrim. Thus just like the latter had placed their votive offering on the shrine of the spirit, so the spirit placed their image into the body of the worshipper.

- The second was called a 'Schabfigur'; loosely translated as a figure to scrape from. Traditionally these were mad of painted clay. The believer would take the figurine home from the shrine of the saint or deity where it had been blessed. There they would scrape of it tiny pieces of dust and sprinkle these over their food, into drinks or even onto the food of their farm animals. Exactly as in the previous method, the idea was that by this act they would take in the spiritual body of the respective saint or deity and absorb their (healing) power within their own bodies.

Before we adore the beautiful images of the first section of the exhibition, let's just put these practices into some further perspective: In the Greek Magical Papyri (PGM) we hear about several rites of deification. One famous method involved the drowning of a hawk in a libation - and the subsequent drinking of this 'enlivened' water by the magician. Most of the PGM stem from the second to fifth century AD; the artefacts featured in this exhibition relate to the 18th and 19th century mainly... Old habits die hard, you may say.

Note: you will find additional commentary for most pictures by clicking on them and hovering your mouse pointer over them.

2. Magic

For a blog on ritual magic, I guess, the artefacts in this section require less of an introduction. Obviously the categories applied here blur in reality - and artefacts of relics, magic, protection and death can all be utilised within a single magical act. However, the below images represent slightly more rare objects and related ritual practices when it comes to traditional European folk-belief.

A truly stunning artefact is the above mentioned Schwurschädel (oath skull). As indicated by its name, such skulls were leveraged in jurisdiction in Medieval times. Throughout times the skull has always been believed to hold magical potency. We can find the act of drinking from skulls and skull cups spread across Europe and the Middle East not only in prehistory, but equally in Medieval and still in modern times (ref. Handwörterbuch des Deutschen Aberglaubens, Band 5, p.202ff). In European lore we hear about talking skulls just as much as about the tradition of bury the skulls of high ranking family members closer to the living than the rest of their bodies - or to keep it even within their homes.

In the particular context of Medieval jurisdiction we see the 'oath skull' replacing the Bible for an official oath. It thus represents an important linkage back to pre-Christian, pagan folk-practices. Rather than vowing by the Christian holy book, the delinquent is asked to vow by their ancestors and with a direct connection to the realm of the dead in mind.

The other object that should be called out is the curious Grimoire depicted on the first image below. Titled in English translation as 'Arcanum Arcanorum Maximum or the true little Jesuit's Venus Book or Coercion' it was only recently discovered in 2014 as part of the preparation for the original exhibition and dates to 1747. On 135 hand-written pages it provides a wild ride through European grimoires, taking from many separate places, all in the determined pursuit of bringing together all spirits who reign over mines, treasures and precious stones and to be man's best companion in the 18th century practice of magical-midnight treasure hunting.

In the companion catalogue to the exhibition Irene Keller's shows her full folk-magical virtuosity and historic scholarship by giving the book a full 15-page in depth analysis. As you can imagine, it provides more than enough material and curious detail to feature in a separate and dedicated post to come...

3. Protection

Obviously this third category is more of a sub-genre of the previous two. Both magic and relics are heavily used in folk-practice to create spiritual boundaries, protected spaces or to attract forces of healing. However, the below artefacts of the exhibition are so unique they deserved to feature in a chapter of their own.

bed with magical seals

1962 painting of an actual Austrian box-bed from 1707

In particular let me draw your attention to the photo of the red and heavily adorned bed frame below. The image is a drawing of an actual box-bed from the early 18th century that makes heavy use of pentagrams and seals to protect its sleeper. Studying this photo in details tells us equally much about the magical knowledge and artistic skills that went into such artefacts three hundred years ago - as well as about the assumed immediacy and power of the evil spirits people at the time thought they required protection from.

Secondly, the three-pieced wooden pendant is of significance (4th photo below).

In fact it was an image in a newspaper of this particular object that made me drive the long way from my hometown to visit Mrs. Keller and her cabinet of curiosities. If only the average magician today would still put so much care, time and skill into their paraphernalia as our much lesser educated folk-magic ancestors did several centuries ago. Yet, as Mrs. Keller pointed out to me, this curious object might have equally been born from a love for detail - as well as from the shier amount of life-angst of its owner: It is a particular good example of 'cumulative protection' in folk-magic.

This special pendant brings together a wide array of magical formulas of protection that originally were not related, but meant to work in concert here to provide even stronger protection to its carrier. Next to a wooden cross we find the SATOR formula which was employed against fire and demons, the pentagram (German, Drudenfuß) which warded off curses of devils and witches, as well as the Blessing of St.Benedict (Crux Sancti Patris, Benedicti Vade Retro Satanas) which was supposed to work counter the devil and all sorts of misery - rounded off by several kabbalistic God names on the outer perimeter (e.g. Adonay).

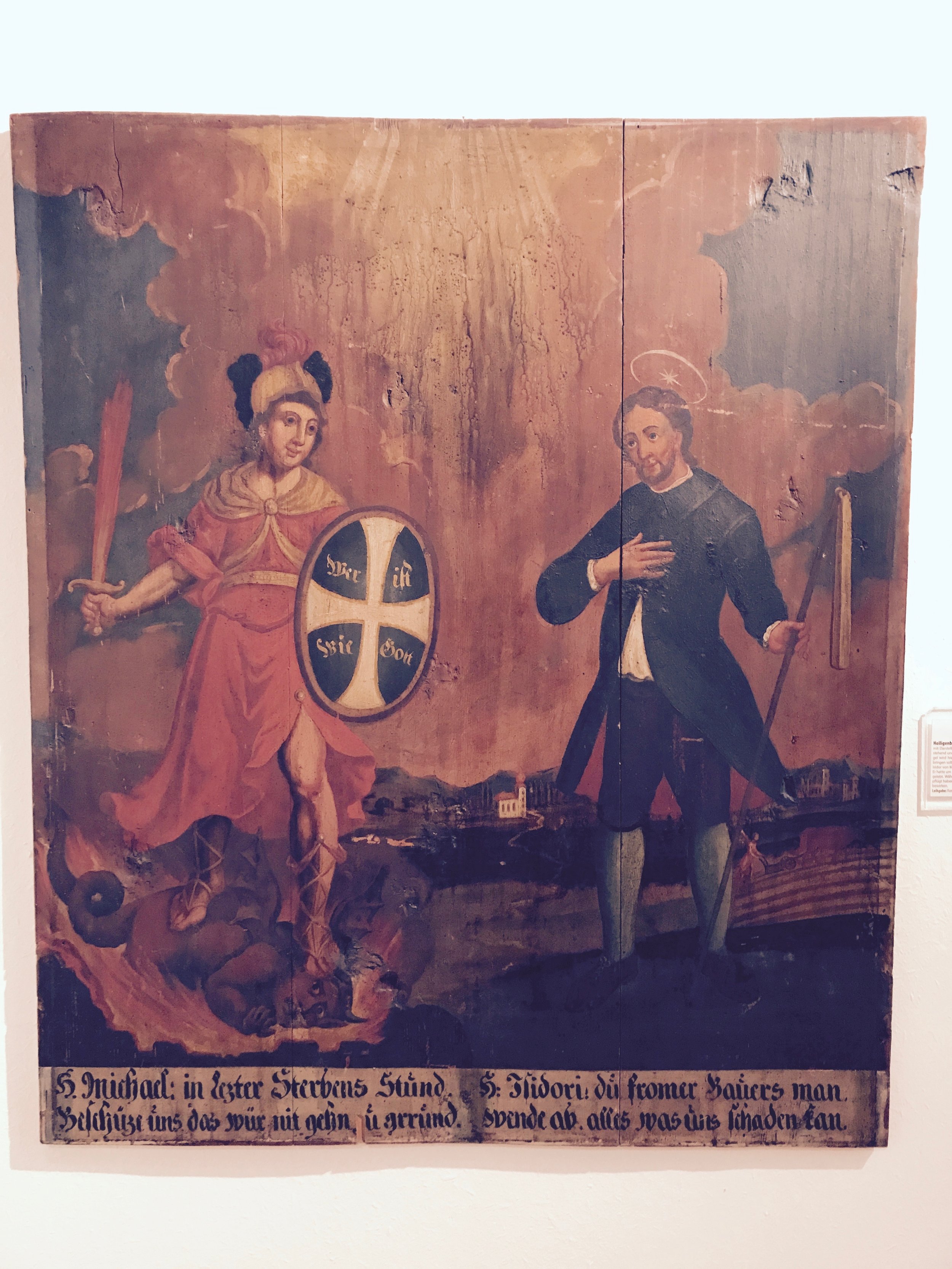

4. Death

Now here is our final 'virtual room' of the wonderful exhibition in the Kulturgut Hausruck. How fitting to end with death. Yet, let me point out that these images and explanations are only a small portion of what Mrs and Mr Keller were able to curate and recover from the shadows for this rare treat. If you have any chance still visiting South of Germany or Austria before October 2017 - you know what to do...

Following my recent exploration into the origins of Goêteia this was the aspect I was personally most interested in. And once you begin digging - or in this case more appropriately: stand in front of the glass cabinets and take it all in - the wealth and richness of folk-believes and -practices relating to dead souls, ancestors, the underworld, and death as a spirit in particular is nothing but breathtaking.

Most of the methods and models we know by hard from more 'pure' sources of ritual magic we can rediscover here in our own European lore: May this be the role of the soul guide (psychopomp) into the Underworld as illustrated below by the archangel Michael with his flaming sword, or the concept of burying the magically potent skull separated from the body of the dead - ideally much further away from the village in a dedicated 'bone home' (Gebeinhaus), or maybe the idea to maintain altars and memento mori shrines for the dead within one's own home. Because a home where the living remembered the dead and paid them their just honour, would not need to be haunted by the dead to call for justice...

The relationship of our ancestors to their own was truly bitter-sweet. While the dead on the one hand were recognised and respected as powerful, magical agents of the underworld and spirits tied to one's own through blood - they were also feared and complimented with subtle mechanisms and techniques not to come back and haunt the living.

Maybe one of the most fascinating examples of such bitter-sweet relationship can be seen in the folk-practice of adorning the corpse with a special crown while on their way to the burial. In a ritual act the dead was venerated as a noble, almost royal spirit. Just to ensure that by paying such homage to them while on their way into the Underworld, this is where they would stay.

We like to say 'you only get one chance to make a first impression'. I guess our ancestors still knew, you also only get one chance to make your last.