An Example of the Olympic Spirits in Folk Magic

I. The Olympic Spirits.

Paracelsus (1493-1541) coined the term of the Olympic Spirit(s) in 1531/1532 when he wrote De causis morborum invisibilium, which was printed posthumously in 1564. He expanded on the nature of these spirit(s) in his opus magnus, the Philosophia sagax, written in 1537 and first printed in 1571. Four years later, in 1575, the Olympic Spirit(s) received the ‘grimoire treatment’ with the original publication of the Arbatel.

From this moment onwards in the late 16th century and all through the 17th century, the Olympic Spirit(s) quickly established themselves at the heart of the learned tradition of Western Magic. They were adopted into the evolving currents of Solomonic Magic, Rosicrucian Magic, as well as soaked up by the broad, meandering river delta of Western folk magic.

Unsurprisingly, what was remembered about the Olympic Spirit(s) in these various traditions of magic were not the intricate mago-medical considerations with which Paracelsus originally introduced the term in the 1530s. Instead, the spirits were uprooted from their Paracelsian soil and truncated to fit the general mould of technical grimoires. What we are left with, in most cases of their appearance across the 17th- and 18th-century textual traditions, are their alleged names and seals, as they first appeared in the Arbatel.

In my upcoming book Holy Heretics (Scarlet Imprint, 2022) I am attempting to restore the Olympic Spirit(s) in their original magical context and ritual purpose. Already in 2020, I shared a first online addendum to the finished manuscript of Holy Heretics, where we examined the seal construction of the Olympic Spirits.[1] Here I am offering a second brief addendum: A largely unknown example of how the Olympic Spirits were pragmatically incorporated into the ever evolving strands of folk magic.

II. The Manuscript Cod.Mag.66

The passage itself is taken from the manuscript titled “Magia de Furto” (Magic of Theft) and registered as Cod.mag.66[2] in the unique Leipzig collection of grimoires.[3] The whole collection was acquired by the Leipzig University in 1710. Cod.mag.66 was identified as a translation from an earlier Latin text, thus should be dated to the late 17th-century or possibly earlier.

It was first spotted by Adolf Spamer (1883-1953) to contain a reference to the Olympic Spirits. Still a figure overlooked in English-speaking countries, Spamer was a preeminent scholar in establishing both the field of German Volkskunde (Anthropology) as well as specifically the academic research on the grimoire tradition. His 23,000 item strong slip-box collection “Corpus der Segen und Beschwörungsformeln” (Corpus of Benedictions and Conjurations) contains an unparalleled number of transcripts of benedictions, conjurations, charms, amulets, celestial letters, and letters of protection dating from the Middle Ages to the 1960s.[4] The current excerpt forms part of the collection under the keyword ‘Confronting Thieves’ (Diebsstellung – III C1).[5]

A full translation of the “Magia de Furto” is still outstanding. From an initial overview, though, it keeps the promise made by its full title: MAGIA DE FURTO this is various secrets to keep one’s things from thieves, to banish thieves so that they have to bring back the stolen good, also to torment and damage such [people] in various ways.[6]

Accordingly, Bellingradt and Otto in their first full survey of the Leipzig grimoire collection give the following summary:

Cod.mag.66 is all about protecting one's goods from thieves, regaining stolen goods, and punishing or torturing thieves by different procedures. These include the use of protective prayers, sigils and charactêres, various types of divination, and the construction of a sophisticated figurine of the thief. The technical terminology used throughout the text reveals that the text has been translated from Latin, and a Latin reader has indeed amended lengthy commentaries – which include alternative recipes – in the margins of some pages. Some of the recipes in this book resemble prescriptions in the nineteenth century German compilation Romanusbüchlein.[7]

III. The Olympic Spirits as Lares

What makes this example stand out from the broad array of appearances of the Olympic Spirits in 17th to 19th-century folk magic is their explicit use as household deities or lares as the original Latin term.

As we can see from the below translation, their application is both innovative as well as eclectic: Three of the seven Olympic Spirits are assigned to specific rooms or spaces in and around a house. Following common practice, known already from Archaic Greek and Jewish traditions, their names and brief conjurations could have been written directly on the crossbeam of the respective door, or on a paper-note which then was fixed there or slipped into the wall.[8]

In a seeming act of apotropaic magic Aratron, the Olympic Spirit assigned to Saturn, is asked to guard the domestic places that otherwise would be considered most vulnerable to the negative impact of Saturnian forces, i.e. loss, hunger and poverty. Thus, Aratron is asked to protect the kitchen, larder, and all other locations where food for animals are stored.

Bethor, the Olympic Spirit associated with Jupiter, finds a more traditional application and is asked to guard the study – the traditional place of domestic learning, writing and reading.

Finally, Hagith, the Olympic Spirit associated with Venus, is asked to protect the domestic locations of rest, renewal, intimacy, as well as – if ever practised – of incubation and dream-magic.

The short excerpt below refers to this practice as given by an anonymous “theologus” at an unspecified time in the past. While it is positioned as a practice explicitly against thievery, the text also recognises the three Olympic Spirits as general “laribus domesticis” (domestic spirits/ household deities/ hearth god/goddess). Therefore, it does not seem unlikely that this magical practice was originally intended to establish general dominion and protection of the respective Olympic Spirits over the respective locations. However, it found inclusion in the current manuscript through a distinctly utilitarian perspective – that is, the classical lens of all folk-magic – and was narrowed down to the pragmatic use of warding off thieves.

As such, the excerpt can be read like a typical specimen of ritual folk-magic: It still shows echoes and outlines of a once more coherent and professional creative process of spirit-partnership. Yet, in its present form, it places the accessibility of the practice, the immediacy of the effect, and the utilitarianism of the layman above all else.

Further studies should examine how Olympic Spirits in Western folk-magic came to displace traditional household guardians such as goblins or brownies from their ancestral positions. What exactly conditioned the belief in the higher efficacy of these relatively unknown spirits, who had only recently been introduced into the pantheon of German folk magic?

Finally, as I have shown in Black Abbot · White Magic (Scarlet Imprint, 2020), several of the manuscripts in the Leipzig grimoire collection appear to be copied from Latin documents today kept in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. Could a thorough search in their archive reveal the original Latin source of Cod.mag.66? If so, it might allow us to retrace one of the pathways the Olympic Spirits took to arrive in the broader river delta of German folk magic.

IV. Excerpt of Cod.Mag.66

English Translation

Chapter.1

How one should keep his things from thieves, so that they cannot steal anything, nor carry away the stolen good.

1.

A certain theologian has [missing] ago recommended a proven means to keep one’s things from the thieves, to command the laribus domesticis [i.e. domestic spirits / household deities / hearth god/goddess]. Therefore, during Easter he entrusted his property to those angelic choirs in the following manner. E.g.

Over the kitchen he used to write as well as over the cellar, pantry, granary, and hayloft the following:

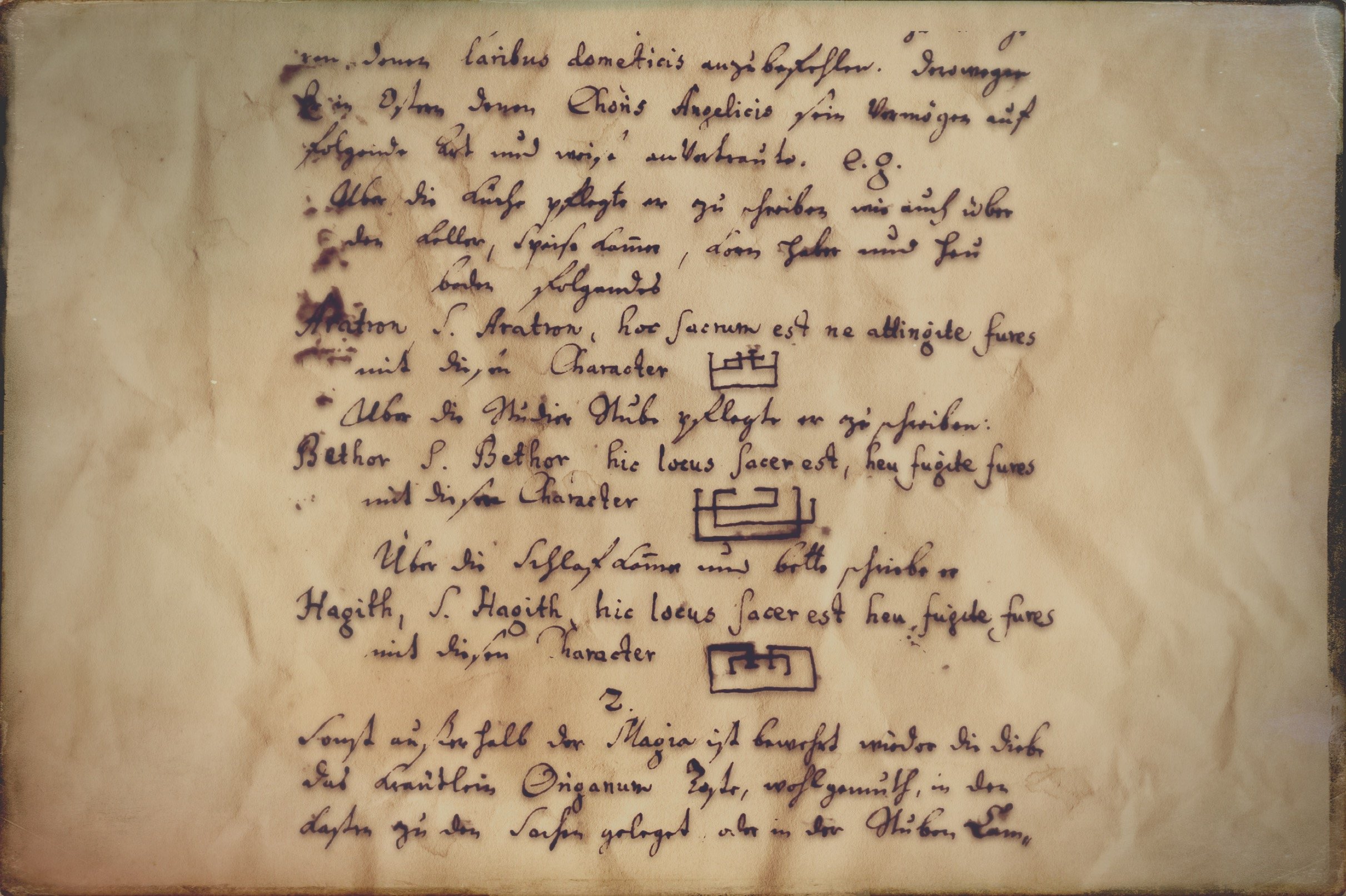

Aratron, S. Aratron, hoc sacrum est ne atlingite fures [this [place] is sacred, lest thieves snatch away], with this character: [seal of Aratron]

He used to write over the study room: Bethor, S. Bethor, hic locus sacer est, heu fugite fures [this is a sacred place, alas, it will drive away the thieves], with this character: [seal of Bethor]

Over the bedchamber and bed he wrote:

Hagith, S. Hagith, hic locus sacer est heu fugtet fures [this is a sacred place, alas, it will drive away the thieves] with this character: [seal of Hagith, inverted]

German/Latin Transcript

Cap.1

Wie man seine Sachen soll vor den Dieben verwahren, dass sie nichts können stehlen, noch von dem gestohlenen Gute fortbringen.

1.

Ein gewisser Theologus hat vor … ein bewährtes Mittel rekommandiert, seine Sachen vor den Dieben zu verwahren, denen laribus domesticis anzubefehlen. Deswegen er in Ostern denen Choris Angelicis sein Vermögen auf folgenden Art und Weise anvertraute. E.g.Über die Küche pflegte er zu schreiben wie auch über den Keller, Speisekammer, Kornhaber und Heuboden folgendes:

Aratron, S. Aratron, hoc sacrum est ne atlingite fures, mit diesem Character

Über die Studierstube pflegte er zu schreiben: Bethor, S. Bethor, hic locus sacer est, heu fugite fures, mit diesem Character

Über die Schlafkammer und Bett schrieb er:

Hagith, S. Hagith, hic locus sacer est heu fugtet fures mit diesem Character

Footnotes

[1] Frater Acher, The Arbatel Sigils Deciphered, theomagica.com, 2020, https://theomagica.com/the-arbatel-sigils-deciphered

[2] https://histbest.ub.uni-leipzig.de/receive/UBLHistBestCBU_cbu_00000089

[3] https://www.ub.uni-leipzig.de/aktuelle-ausstellungen/zauberbuecher-die-leipziger-magica-sammlung-im-schatten-der-fruehaufklaerung/ – for an indexed list of the grimoire manuscripts included see: http://studies-vartejaru.blogspot.com/2013/08/complete-list-of-leipzig-university.html

[4] Available for digital access in German: https://www.isgv.de/projekte/volkskunde/erschliessung-und-digitalisierung-des-nachlasses-adolf-spamer/corpus

[5] Accessed on 01/07/22: http://digital.slub-dresden.de/idDE-611-BF-67803

[6] MAGIA DE FURTO das ist Unterschiedene Geheimnüße, Seine Sachen vor dieben zu verwahren, diebe zu bannen, daß sie den diebstabl müßen wiederbringen, auch solche auf unterschiedene art zu peinigen und zu lædiren.

[7] D. Bellingradt and B.-C. Otto, Magical Manuscripts in Early Modern Europe, Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017, ISBN 9783319595245, with an open access appendix: THE CATALOGUS RARIORUM MANUSCRIPTORUMhttps://link.springer.com › bbm:978-3-319-59525-2 › 1.pdf

[8] For further reference on the magical use of doors see for example: (1) Hanns Bächtold-Stäubli (ed.); Handwörterbuch des deutschen Aberglaubens, Augsburg: Weltbild, Band 8, 2000, columns 1185-1209, (2) Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa; Three Books of Occult Philosophy, Book 1, Chapter 42, Rochester: Inner Traditions, p.140-141, (3) Pliny the Elder, The Natural History, Book 28, Chapter 27, (4) Aletta Seifert; Der Sakrale Schutz von Grenzen im Antiken Griechenland - Formen und Ikonographie, Freiburg, 2006