72 Devils' Seals by a 17th-century Goës

Introduction

Historical research in the field of the occult is a strange thing. It requires an equal measure of openness to deviate from preconceived itineraries, as well as determination not to be seduced by the lure of ubiquitous anecdotes. All too quickly, a curious aside can take on a life of its own. Like a walk in the woods at night, we find ourselves surrounded by strange noises and a wide-open space that invites further and further exploration. The unknown wishes to be discovered. The ambiguous wishes to be clothed in form and story. And yet, every little anecdote can become another step into the labyrinth of spirits, and a step further away from arriving safely.

While researching the History of the Olympic Spirits, I came across the following curious historical footnote. I share it here because it seemed too valuable not to make it accessible to a wider English-speaking audience. However, as with so many texts of folk-magic, its real value lies not in the fancy spirit seals, but in the implicit information it conveys about the practice in question.

Luckily, its backstory has been preserved for us by the Austrian historian and archivist Hartmann Ammann (1856-1930) in his short essay The Sorceries of Ludwig Perkhofer von Klausen, including the use of Devils’ Seals (Hartmann Ammann; Die Zaubereien des Ludwig Perkhofer von Klausen mit Anwendung von Teufelssiegeln, in: Forschungen und Mitteilungen zur Geschichte Tirols und Vorarlbergs, 1917, p. 66–77).

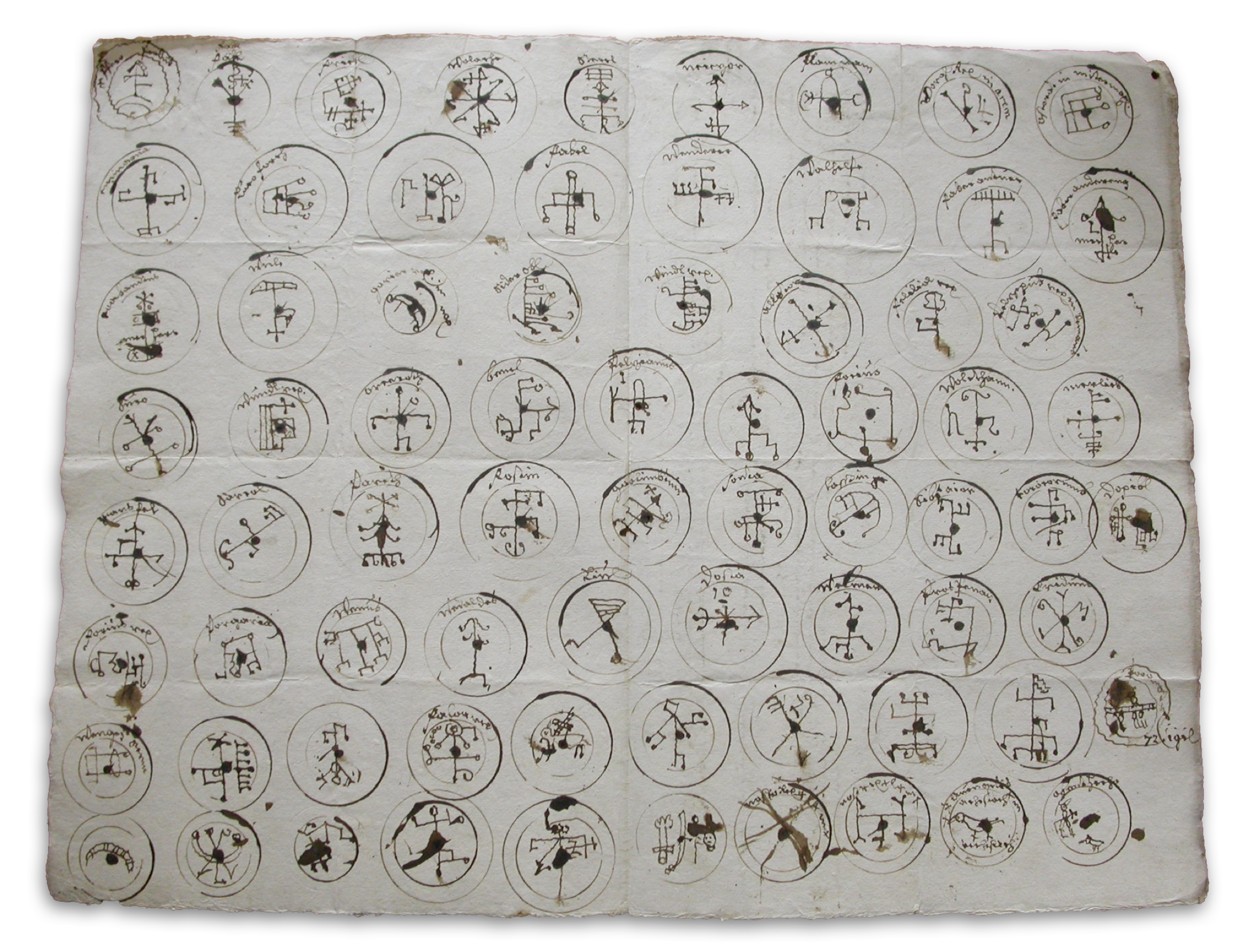

Ammann included in his article a coarse photograph of the devils’ seals. We are extremely indebted to the Director of the Diocesan Archives of Brixen, Erika Kustatscher, for the new photos that she has made available and which are reproduced here.

Ludwig Perkhofer, a 17th-century Goês

On May 31, 1681, the dean of the cathedral and auxiliary bishop of Brixen, Jesse Perkhofer, had died. Still at his deathbed, the bitter fight of his brother, Ludwig Perkhofer, for the rich estate of the bishop, which is said to have amounted to 35000 imperial florins, developed.

During this legal dispute, Ludwig confronted his opponents in such a polemic and accusatory manner that it was quickly suggested to imprison him. While he escaped an official verdict of incarceration, he was subjected to an interrogation in order to determine whether the statements and invectives in his writings, which sometimes bordered on blasphemy, had originated from his own hand, what he had actually wanted to achieve with them, and whether he was prepared to retract the complaints that had been made.

Additionally, an order was given to confiscate a certain chest from Ludwig and to inspect its content. As the surviving protocol in the Brixen archive detail, within it the officials found: Two old, written books on various “arts”, an incantation of the evil spirit, two other books with forbidden arts, an incantation for finding treasures and mines, an incantation of the chicory root, a number of written slips of paper, including one with circles and names of saints, a booklet on how to solve sorceries; furthermore, in the small chest were found: a mirror for an unknown purpose, and in a small bag hoopoe heads and several iron nails.

Despite these highly suspicious objects, and only after the intervention of Ludwig’s son with the bishop, his father was released from pre-trial detention, but with some strict conditions such as being sent to a small mountain village three walking hours from the city of Linz and needing to remain there, as well as to forgo all previously mentioned claims.

Although he accepted these conditions under oath, he continued to fight for the inheritance of his deceased brother. And so, we find our stubborn Ludwig in custody again already during the same year, 1682. This time, the protocol reveals some further glimpses into his magical practice:

Ludwig Perkhofer confesses that he had conjured his deceased brother (the suffragan bishop) to appear before the commission at the hearing about his estate and to testify in his (Ludwig’s) favour. Ludwig had even added: “And you God, when you are a just God, must let the appearance happen.”

He never bothered with certain arts and conjurations of devils, nor did he ever need their help. He himself painted and wrote the seals and invocations of the supreme devils with their characters, names and signs [...]. He received the manuscript for copying from N. Tassenpacher from Prague, copied the incantation only out of curiosity and for the science of how to fix the devils, but never made use of it. He did not have the characteres (devil seals) in a special depository, but in a sack with various writings and has had them for 8-10 years.

Ludwig Perkhofer also had 2 written books, in which different such forbidden arts were inscribed, he received them from the two daughters of the old doctor who died in Taufers, read them through, but never used them. He used the roots of the chicory and conjured it that, when something was stolen from him, he put such roots under the pillow and then the thief “dreamed” him, and once in Taufers a thief brought him back chains and belts. He performed the incantation with the words: “I adjure you root by the living God with those powers, so you have been gifted by God, that you communicate the same power to me.”

He did not use the booklet for resolving sorceries, and he did not exercise the mirror that leads to the mines, because he did not conjure it to this end.

He wanted to use the hoopoe heads only for the poison, together with the iron of old horseshoes that one finds on the road, with which one makes the mines invisible or cancels their invisibility.

He did this once on the Albl, called Jaghaus behind Rein [a side valley of Taufers near Brunecck]. In the evening it did not work, but when he tried again early in the morning before sunrise, he found the lost mine again in the following way:

That he put the nail in there [?], then took three steps behind him and said with each step: “With the nail I have bound you, with the nail I open you, God the Father, Son and Holy Spirit help me.” After finding the mine in this way, he also made it invisible again by going three steps behind him and saying at each one, “Nail, as long as you don’t get back into the hole from which I pulled you, no one shall find you in the name of God the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.”

Ludwig Perkhofer does not know where he learned this art, but he believes to have read it in a book. Otherwise he knows nothing of these things, “except that he advised people to load such nails into their rifles and to shoot them into the clouds during thunderstorms, which was supposed to be good for sorcery.”

During this second trial, as expected, Ludwig Perkhofer did not get off so lightly. In 1683 he was ordered to make ecclesiastical apologies, sentenced to ten years in prison, and his entire magical inventory was to be burned in front of his own eyes... Clearly the latter step was never taken in full, as the double page with the spirit seals survives to this day in the Diocesan Archives of Brixen (Signatur HA 9891).

These files also reveal that Ludwig Perkhofer, who was already 72 years old at the time, did not bow to this second order, but continued to fight tenaciously for what he believed was either rightfully his or should be his with the help of the spirits he had enlisted. Perkhofer died, still involved in legal battles, before the end of 1685.

The 72 Devils’s Seals

Interpretation

In the following, we provide modern images of these unique spirit seals, as well as a translation of Ammann’s attempt to reconcile their nature and construction.

As we will see, from the perspective of a modern practitioner, the value of this historical material is condensed in the following three points. We anticipate these here to facilitate access to the material that follows:

(1) These spirit seals make no claim to orthodoxy. On the contrary, they probably represent fascinating folk echoes of authentic goêtic practice. Rather than using rubber-stamped seals, the practitioner is encouraged to derive from each spirit a unique interpersonal seal intended only for their communion and contact.

(2) The instructions mention Lucifer as the ruling prince of the operation. However, the actual conjuration says that the spirits are summoned under the power of “him that maketh earthquakes”. Here we have another hint of authentic goêtic practice: Rather than orthodox spirit names, derived from man-made mythologies, the practitioner turns to a nameless spirit-force that is instead described by its specific ecological and chthonic power.

That spirit which holds the power to release earthquakes rules the realm of underworld. It is known foremost by its function in the ecology the practitioner participates in. And for this very reason, because of its elevated and unchallenged position of power in that of the underworld, this spirit is asked to bring the spirit in question into contact with the practitioner.

(3) Very few of the 72 listed spirit names are consistent with or reminiscent of classical Western spirit names such as Ariel, Beelzebub, Venus, or Ostara. Most of the others may be distant distortions of once-classic Western spirit names. Perkhofer himself states that he obtained the sigils from a man in Prague and copied them – which of course might have been a trick he devised during his interrogation to avoid revealing more about his personal practice.

From the perspective of a goêtic practitioner, we should instead consider another possibility: The spirit names on some of the seals might actually be the names of the spirits as revealed to Perkhofer or another local practitioner. This assumption is supported by the fact that some of them refer to actual places in Austria, e.g. Wörgl or Lassing. In addition, some of them are simply subtitled “rex”, meaning “a spirit is the king of”. This suggests that these spirits ruled over certain places such as a village, a mountain, or a gorge. In this case, the seemingly convoluted names below could indicate both actual locations in the practitioner’s topography, as well as personal names revealed to the goês.

Such considerations turn this historic anecdote into a curious case of possibly authentic goêtic practice – in the sense of a lived reality of chthonic sorcery – that took place in the Southern Alps of the 17th century: Spirits were conjured under the auspices of enlivened natural forces, their names were bound into the topographic locations where they resided, and any of the marks and echoes they left behind – may that be in the form of seals or names – were ephemeral and given as unique keys to the individual practitioner.

To invoke them once again today, a new bond must be placed around the minds of man and spirit. Each one unique, coloured by location, time, and order in the cosmos. To the chagrin of the modern scientific mind, nothing in magic repeats itself twice in exactly the same way. Never on this planet have two people kissed twice in exactly the same way. Likewise, no human and no spirit will ever make a bond that is not coloured by the time, topographical location and cosmic order by which they are connected.

Yours is yours and mine is mine. All we can do, is to send a call from here to there, in the hope that ancient ways are revived in modern times.

The Investigation of the Devils’ Seals (Ammann, 1917)

The above-mentioned 72 devil seals or characters are drawn on the two inner sides of an ordinary sheet of writing paper and are distributed in a not quite even manner over 8 lines. They consist of two concentric circles each, drawn in black ink, but not always completely, between which usually the legend of the respective prince of hell is written. The scribe (Ludwig Perkhofer himself, see above) missed one with the legend Naso rex in the last line, which is why he crossed it with several strokes and entered it again next to it.

All seals are heraldic seals. Most of them consist of a number of straight lines, perpendicular to each other in various directions, forming tripods, but also cranes, and often ending in a pommel or an arrow-shaped point. Two seem to represent a perforated document with a seal; only a few contain images of people, animals or weapons, such as birds, a trident (?) a sword, etc.; two represent a caterpillar-like bulge, and in the penultimate row there is even the coat of arms of the city of Brixen, a lamb with a cross, which is probably supposed to represent a flag, of which only one is a flag.

The only visible part of the flag is a tassel hanging down. Since the legends are often written very unclearly, I cannot vouch for the fact that I have always read them correctly; I therefore see the ones that seem uncertain to me with question marks (?).

1. Pfere Pardus (?) 2. Fäbl, 3. Ariel, 4. Wolache, 5. Nerel (?) 6. Neizor, 7. Flamman, 8. Worgl Rex in arem, 9. Ostarat in mitermax, 10. Eminarna (?) 11. Suroforlt, 12. without legend, 13. Fabel, 14. Wenderer, 15. Walhelfe, 16. Faber antuar, 17. Faber andereng above and in the seal field, below “mer Har”, 18. Rua(?) bantes, in the seal field as no. 18, 19. Wüle, 20. Gorian in nox, 21. Siderobl, 22. Windl rex, 23. Alleton, 24. Felibiol rex, 25. Pelzepub rex in Romanis, 26. Suro, 27. Wündl rex, 28. Orneroth (?) 29. Bimel, 30. Pelzianus, 31. without legend, 32. Foriub, 33. Wolthann, 34. Merlieb, 35. Gans (?) fel, 36. Sareol, 37. Pareth, 38. Rosim, 39. Garlimbtun, 40. Sonta, 41. Lassing, 42. Sibtaier, 43. Furororumb (?), 44. Dopiol, 45. Farius rex, 46. Porgaria, 47. Wenus, 48. Wedaldes, 49 Liul, 50. Dostä, 51. Welman, 52. Pro- spenais, 53. Tridum, 54. Wenges gernn (?) 55. and 56. without legend, 57. Falor rex, 58. to 62. without legend, 63. Foroman rex, 64. to 69. without legend, 70. Naso rex XXX in X (seal crossed out), 70. a Naso rex + 1 + in XX, 71. XX Avanzetis? achesach? X in ruhtsech?, 72. Obmt Hecho.

The Application of the Devils’ Seals (Ammann, 1917, quoting the original archive documents from 1685)

These are the 72 seals of the supreme devils, hell kings, and princes. When they are required, take this constraint in your right hand and swear to them, and he will give you his seal. After that, make sure he cannot leave until he does your will and keep the seal.

Summon Lucifer to send the spirits, and if he will not come, take the same seal and write, as the seal is, on a plate that you smear with linseed oil, on it sulfur, [...] and asafoetida pitch, and burn it together with the hair of the goat, which you mix with the sulfur and pitch, until he does your will.

I adjure thee, spirit, by him that maketh earthquakes, that thou burn up this accursed spirit and devil, and make him to be accursed and martyred for ever.

Item speak over the fire and seal this incantation:

O thou [NN], thy name is put to shame, and thy name is incensed, and at the same time is tormented by the brimstone also by Lamoth's working, and reminded anew of thy admonition by the name of Lais Terminorum. You come into your dwelling first by the name Luasein, Laian, Ruriari, Lefeloria vyri, Rarefurth pero [...]. And before you will call the last name, whichever spirit it is, you will see it.

![[close up, top left] 72 Devil's Seals from the trial records of Ludwig Perkhofer, 1683](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/500654d4c4aa3dba7737b978/1656231536137-9LR9RIX2900UIHFPLVCL/Screenshot+2022-06-26+at+10.11.06.png)

![[close up, top right] 72 Devil's Seals from the trial records of Ludwig Perkhofer, 1683](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/500654d4c4aa3dba7737b978/1656231580243-56O6U01CZQM5IVZQQUBU/Screenshot+2022-06-26+at+10.11.12.png)

![[close up, bottom left] 72 Devil's Seals from the trial records of Ludwig Perkhofer, 1683](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/500654d4c4aa3dba7737b978/1656231597604-JR9LB4195ROY2WRCHZ2L/Screenshot+2022-06-26+at+10.11.18.png)

![[close up, bottom right] 72 Devil's Seals from the trial records of Ludwig Perkhofer, 1683](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/500654d4c4aa3dba7737b978/1656231621784-0OBUPI2UY9MCI8D7WFAN/Screenshot+2022-06-26+at+10.11.24.png)